In What Time Periods Had All Living Things Living In Oceans No Land Animals

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/ba/7fbae5fe-aab0-4a33-8839-19aa6a5a30b4/karencarrecologyweb.jpg)

The motion of animals from the land into the sea has happened several times over the final 250 million years, and it has been documented in many different and atypical ways. Simply now, for the starting time time, a team of researchers has created an overview that non but provides insight into evolution, but may too help more accurately assess humans' impact on the planet.

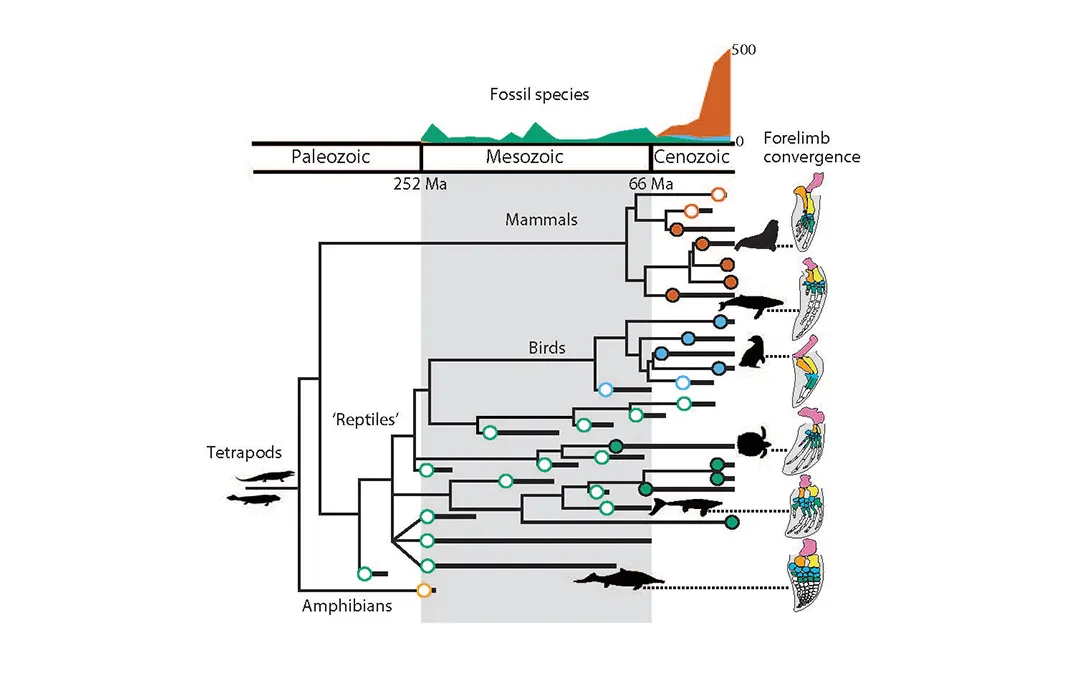

The oceans are teeming with tetrapods—"four-legged" birds, reptiles, mammals and amphibians—that have repeatedly transitioned from the land to the sea, adapting their legs into fins. The transitions have oft been correlated with mass extinctions, merely the truthful reasons are simply partly known based on fossils and through study of Earth'south climate, for instance.

Those transitions are considered to exist "canonical illustrations" of the evolutionary process and thus ideal for study; living marine tetrapods—such as whales, seals, otters and bounding main lions—also have a big ecological affect, co-ordinate to Neil P. Kelley and Nicholas D. Pyenson, the two Smithsonian scientists who compiled the new wait at these tetrapods, appearing this week in the journal Scientific discipline.

Instead of gathering testify from a single field, the pair pulled together inquiry from many disciplines, including paleontology, molecular biology and conservation ecology, to give a far larger picture of what was happening when animals transitioned from the land to the sea across millennia.

Virtually by necessity, scientists tend to work in narrow silos, and so this research will aid broaden their views and potentially make for quicker progress in understanding evolution. Knowing how these creatures adapted over the last few hundred million years, and especially how they've inverse in the era since humans appeared, could help united states of america become better stewards of the planet.

"It'south a 1-of-a-kind summation of all that's known well-nigh those different groups that evolved to go back to the bounding main," says Louis L. Jacobs, a professor of earth sciences and president of the Institute for the Study of Earth and Man at Southern Methodist University. The newspaper lays it all out in a way that allows scientists to make comparisons beyond species, he adds.

"The review actually gets at the heart of evolution and why the study of development is important," says Sterling Nesbitt, an assistant professor of geosciences at Virginia Polytechnic Constitute and State Academy. Nesbitt focuses on vertebrate evolution—not marine animals—but he says that the Smithsonian researchers' work will assist him and his students empathise, for instance, how some land animals may have adapted to being able to live in copse.

The research also "provides the evolutionary context for understanding how living species of marine predators volition evolve and adapt to life in the Anthropocene," says Kelley, the paper'southward lead author and a researcher in the National Museum of Natural History section of paleobiology. He adds that he purposely chose to use the term "Anthropocene" in the newspaper. Some scientists utilize it to depict the current geological era, simply as well to mean that it's a time in which humans seem to be playing a dominant role in the direction of the planet.

"It'southward not only academic to imagine what the fate of these animals might be," Kelley says, adding that marine predators in particular are ecologically important players. "It might accept a big impact if we lose these predators," he says.

The Kelley and Pyenson paper draws from 147 generally peer-reviewed studies in a variety of fields, giving a rich overview of some of the parallel adaptations that occurred amid a number of marine tetrapod species. That's extremely tantalizing, says Jacobs.

Among its many threads, the piece of work highlights a relatively new line of enquiry called fossil pigment reconstruction, a technique that gives scientists the ability to decide, from a fossil, the color of an ancient bird's plume or of a prehistoric reptile's pare. Coloration can provide clues to the means species adjust to their environment. One study, for instance, revealed that ancient marine reptiles had dark coloration, "possibly for temperature regulation or ultraviolent lite protection," the researchers write.

Genomic studies are as well helping to piece together the reasons marine animals with unlike land ancestors appear to take developed like adaptations when they went into the ocean, according to the authors. For example, both beaked whales and seals have evolved to have the power to store myoglobin—an oxygen-binding protein—in their muscles. This gives the deep divers the ability to survive underwater for long periods of time. Prior to genomics, scientists had non been able to trace that similar ability downwards to a molecular level, says Kelley.

But now, they tin see that these unlike types of sea divers may accept the same cellular mechanisms. "In that location'southward a deep evolutionary connectedness at that place," says Pyenson, curator of fossil marine mammals at the Natural History Museum. The question at present is whether genetic sequences tin be tied to specific behaviors or body type, or breathing ability, or fin evolution. "Nosotros don't know nevertheless, but we might in the next five years or so," Kelley adds.

The review also pulls together various studies that evidence humans' impact on tetrapod evolution. Humans accept hunted a variety of tetrapods almost to extinction, and human activity seems to exist indirectly hastening the disappearance of others. Six of 7 ocean turtle species are threatened. And the Yangtze River dolphin, establish only in that river in China, was declared extinct in 2006 as a consequence of shipping accidents and habitat degradation.

But some tetrapods have outwitted humans. Gray whales, which were thought to live merely in the Pacific, have recently been found in the Atlantic. "The best guess for how they got there is they are moving through the Arctic," says Kelley, noting that the water ice has melted enough to allow a waterborne passage. The fossil record shows that gray whales once lived in the Atlantic some 100 million years agone, and so their motility back may be a recolonization process, Kelley says.

Kelley and Pyenson promise that their paper motivates more than collaborations, for example, among paleontologists, biologists and conservationists, to bring the past and the present together—especially to take a closer expect at marine animals. Humans "are having an outsize bear upon on the future," says Pyenson. The review helps reply the question of "what is going to exist the fate of these ecologically of import species?"

"Understanding the ocean is vital for humans on this planet," says Jacobs, noting that it plays an important part in the ecosystem. But he adds that humans are changing the ocean—leading to rising sea levels and ascent temperatures, as well equally changes in salinity and acerbity, all of which are stressing animals. "We don't know all the unforeseen consequences of what these physical changes volition bring most."

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/take-deep-dive-reasons-land-animals-moved-seas-180955007/

Posted by: beasleydody1988.blogspot.com

0 Response to "In What Time Periods Had All Living Things Living In Oceans No Land Animals"

Post a Comment